|

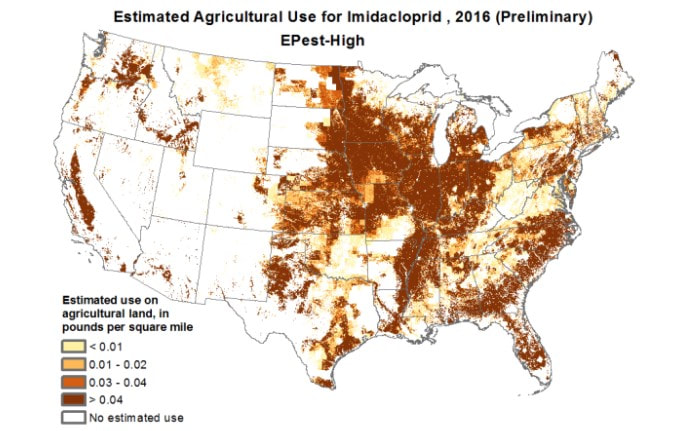

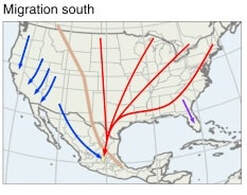

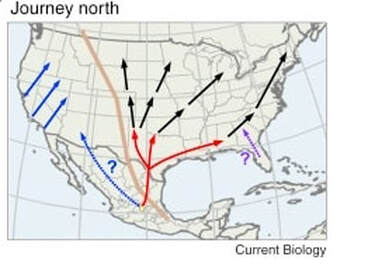

Monarch Butterflies are amazing and in trouble. People who are trying to help them can actually do more harm than good if they’re not careful. Let's take a closer look at the weird, wonderful world of Monarch Butterflies.  The Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus) is a truly wonderful creature, famously migrating thousands of miles to the mountains of Michoacan, Mexico where they spend the winter and breed. Their children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren (sometimes even to the 5th generation) work their way back north to their ancestral summer homes, following the sun as a compass, using an internal (Circadian) clock in their antennae(!) to adjust for the daily movement of the sun across the sky. All this with a brain the size of a pinhead!  They take it relatively easy on the return trip, timing their journeys so they can lay eggs on emerging milkweed that the caterpillars then feed on as the spring rolls northward. This in itself is amazing, because Monarchs have evolved to feed on otherwise toxic plants (the “milk” in milkweed is a cardiac glycoside), which makes the juicy caterpillars thoroughly disgusting to any bird that dares to take a bite. Monarchs west of the Rockies prefer to spend the winter on the California coast, where they can make direct flights, rather than the multi-generation roundtrip to Mexico. But they’re no less amazing and in just as much danger. Overall, Monarch populations are down about 80% from where they were in the 1980s, mostly due to changes in farming, but also from habitat loss and (coming up fast) climate change. Farmers used to leave hedgerows on the edge of their fields (a remnant of the response to the 1930s Dust Bowl) that provided habitat for weeds, including milkweed. These have largely been eliminated to maximize production and profit.  Western Monarchs have declined as much as their brethren. The first count by the Xerces Society volunteers (https://xerces.org/monarchs) in 1997 found 1¼ million butterflies; this was likely already significantly down from previous decades. In 2020, fewer than 2,000 western Monarchs were spotted; they’ve bounced back to nearly 250,000 this winter, but the trend is bleak. The huge masses of Monarchs that cover trees are found mostly between Santa Cruz and Santa Barbara, but ten thousand used to hang out at UCSD, with thousands more at sites from Carlsbad to La Jolla, and even hundreds in Balboa Park. This winter, none of these places counted in the double digits, except for Torrey Pines (91), and strangely, a tomato field at Camp Pendleton, with a thousand. The #1 thing you can do to help the Monarch butterfly is to eat (and wear) organic, thus reducing the acreage of agriculture fields using neonics and providing more safe places for the caterpillars to feed. But most of us want to do something more direct, where we might actually see the butterflies we’ve saved flying around our yard. So head right over to your local garden supply store, buy some milkweed plants, and wait for the Monarchs to show up, right? It’s a bit more complicated.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |